Algiers – Accused of heresy by Islamist extremists and targeted by the authorities, members of Algeria’s tiny Ahmadi community say they have been forced to go underground to worship.

Abderahmane, a 42-year-old trader from Kabylie in northern Algeria, joined the reformist Islamic movement after years as an ultra-conservative Salafist.

People he once called friends reported him to the local imam, who publicly denounced him as an unbeliever.

The imam went on to urge worshippers not to let their children play with Ahmadi children.

“My sister’s engagement was cancelled because her fiance was told I was an unbeliever,” Abderahmane said, still wearing a well-trimmed beard, a long cotton shirt, and three-quarter-length trousers – the garb of his former life as a Salafist.

Founded in late 19th-century India, the Ahmadiyya movement follows the teachings of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, an Indian Muslim they believe to be the long-awaited Islamic messiah.

It is anathema to traditional Islamic thinking, and Ahmadis living in many Muslim-majority countries have faced persecution and physical violence.

While Ahmadis consider themselves to be Muslims, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation – of which Algeria is a member – declared in 1973 that the movement was not linked to the Muslim faith.

Nonetheless, the faith’s strong missionary drive has gained it an estimated 10 million members in 190 countries around the world.

The movement didn’t begin spreading in Algeria until 2007, when an Ahmadi satellite television channel reached the north African country.

After that, they worshipped freely, if discreetly, for a decade. Few in Algeria had even heard of Ahmadism until last year, when the government crackdown began.

‘Israeli plot’ claim

Ahmadi leader Mohamed Fali, a 44-year-old shopkeeper, was arrested in June 2016 along with his deputy, shortly after applying to register a charity. Police searched their homes and confiscated their passports.

Since then, Fadi says 286 out of Algeria’s roughly two thousand Ahmadis have been arrested. All but three have been handed jail terms, ranging from a three-month suspended sentence to four years. The other three received fines.

Most were convicted of breaking right to assembly laws – but their lawyers say they have been persecuted simply for their faith.

Islam is the state religion in Algeria, where Sunni Muslims make up the majority.

Freedom of religion is guaranteed by law, but preachers and places of worship must be licensed by the government. The Ahmadis have never applied for such a status, believing they would face certain rejection.

In July, Algeria’s Religious Affairs Minister Mohamed Aissa told journalists the Ahmadis were involved in a plot by Israel – where the community are allowed to worship openly, with a big mosque in the city of Haifa and a television channel – to destabilise the country.

The minister at first agreed but later declined to talk to AFP.

Sirine Rached, an Amnesty International researcher, said the accusations were “baseless” and accused the Algerian government of a crackdown that is unprecedented in the wider region.

“As far as we know this persecution of the Ahmadis in Algeria is a unique situation in the Maghreb,” she said.

Praying in secret

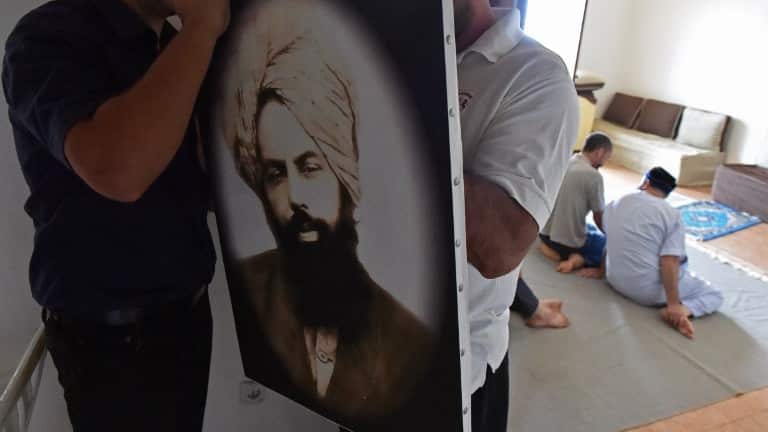

Fearful of harassment by Islamists or the authorities, Algeria’s Ahmadis meet to worship at each others’ homes – including Fali’s house in Tipasa, west of Algiers.

Around 20 prayed in the large living room, adorned only with an imposing portrait of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad.

Fali began proceedings with the Islamic confession of faith, and he emphasised that the Koran was the Ahmadis’ holy book.

The worshippers – among them engineers, doctors and students – refused to give their full names or be filmed.

All of them said they have gone through a crisis, questions and doubts, to which Ahmadism had provided the answers.

“As a modern woman, I can say that Ahmadism has brought me closer to God,” said lawyer Nadia, 49.

Their creed teaches non-violence, and also advocates the separation of state and religion – a vision disputed by Islamists, particularly the ultra-conservative Wahhabist version of Islam exported by Saudi Arabia.

“The debate should not be about Ahmadism but about freedom of worship,” said Hamid, one of the group.

Fali, who is awaiting trial on charges ranging from “unauthorised collection of donations” to “offending the Prophet”, said the Algerian media had “distorted the practices of the Ahmadis and tried to portray them as non-Muslims”.

The campaign against the group is political, he said, pinning the blame on Wahhabists and the Saudi establishment.

Salah Dabouz, the movement’s lawyer, agreed.

“The Ahmadis threaten their ideology by advocating secularism and non-violence in the name of Islam,” he said.