Inside the Bait-ul Qadir mosque on Fond du Lac Ave., a small group of men gathers before the midday prayer. They speak of the weather, their families, the inanities of daily affairs — but also the great mysteries of life and the path to salvation.

“We are what we do. And in the next life, we will be judged by our actions,” said Rashid Ahmad, an imam, who at 90 commands the quiet respect of his fellow worshippers.

“You cannot judge a body that has been in the ground; it is dust. But your actions…,” said Ahmad, waving his hand as if to cast a fine powder into the ether. “Your actions are still here.”

Assembled in this way during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, discussing the teachings of the Prophet Mohammed and their sect’s founder Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, could amount to a death sentence in some parts of the world. But the Masjid Bait-ul Qadir is on Milwaukee’s north side, where members of the local Ahmadiyya Muslim community — one of the oldest in the country — are free to worship as they please.

“We are just like other Muslims in that we follow the teachings of the Prophet Mohammed, the way we worship and the five basic pillars of the faith,” said Rizwan Ahmad of New Berlin, one of the leaders of the local mosque.

“The only difference is we believe that the messiah who is awaited by most of the major religions — other Muslims, Christians and Jews — has come in the person of our founder.”

For many mainstream Muslims, who are predominantly Sunni or Shiite, the small Ahmadiyya sect is one of heretics. Ahmadi are persecuted, even killed, in places such as Pakistan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia. And while there has been isolated violence in the United States — an Ahmadi man was murdered and a mosque torched in Detroit in the 1980s — difficulties locally have been described mostly as minor tensions, a heated debate among college students, or a personal slight at a gathering.

An offshoot of the Sunnis, the Ahmadiyya movement was founded in India in 1889 by Ghulam Ahmad, who declared himself the second coming of Jesus and the divine guide foretold in the Qur’an.

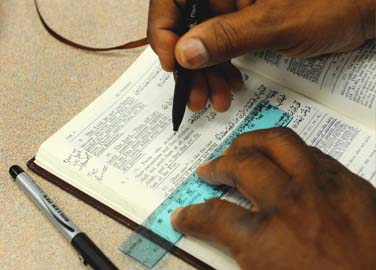

Led by the now London-based Khalifa Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, the Ahmadi stress tolerance and nonviolence, preferring — as they like to say — the “jihad of the pen to the jihad of the sword.”

Though worldwide numbers are difficult to come by because of their persecution, the sect is estimated to have as many as 20 million adherents in 200 countries, said Qasim Rashid of the Washington-based Ahmadiyya Muslim Community USA. The American community, founded in Chicago in the 1920s, has more than 15,000 members, he said.

Milwaukee’s Bait-ul Qadir mosque — in the former corporate headquarters of AAA Wisconsin — is a reflection of the Ahmadis’ global scope and their nearly 100 years of history in urban America. Its 300-plus members include those born to the faith, in families that emigrated from such places as Pakistan, India and Indonesia, but also many converts, mostly African-Americans.

“We’re a very diverse group,” said Rizwan Ahmad.

About 80 members gathered for Friday prayers, many bringing food for the poor, and fasting as the Qur’an requires during Ramadan.

“It’s such a spiritual experience; I look forward to it every year,” said 71-year-old Aziza Ahmad.

Each night during Ramadan, after they’ve gone to bed, Ahmad and husband Rashid rise to recite the tahajjud, or night prayer.

“You have to put your whole soul and being into it…to please your creator,” she said. “You really have to pour your heart out and be grateful for what he’s done for you.”

Rashid, of the national Ahmadiyya organization and author of the book “The Wrong Kind of Muslim,” testified last week before the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom about the persecution of the Ahmadiyya in Pakistan. There, he said, the Ahmadi faithful are blocked from voting, discriminated against in most aspects of society and targeted for murder by extremists.

Local adherents know it all too well. The brother-in-law of Rizwana Imran, who emigrated to the United States 14 years ago, witnessed the carnage when Taliban gunmen slaughtered 86 people in a Lahore mosque in 2010, she said.

Qudrat Ullah Ayaz, who came in 2003, recalled his degrading treatment once colleagues at a tech firm in Pakistan learned he was Ahmadi.

“I was told I could not eat with them. My food, my water, my glass, everything had to be separate,” he said. “That time, I felt that I was an animal, that I am not a human being.”

It is not the Ahmadi way, members said, to retaliate.

In fact, since the terrorist attacks by Muslim extremists in the United States 2001, the American Ahmadiyya community, including the Milwaukee branch, has campaigned to promote the faith’s emphasis on peace.

Ahmadi in Milwaukee and around the country contributed thousands of pints of blood in recent years in the Muslims for Life campaign, which takes place again in September. They’ve taken out ads declaring there is no conflict between loyalty to Islam and loyalty to the United States.

They’ve made a concerted effort to reach out to other Muslims and the interfaith community, and plan soon to launch a new campaign titled: “Mohammad Messenger of Peace.”

“Our goal is to find a way to build bridges, not pick fights,” said Qasim Rashid of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community USA. “You do that by connecting with people on a human level and helping them understand that we have more in common than we have differences.”