As I casually scrolled through my Facebook newsfeed one morning, I stumbled across an Al Jazeera English post linking to an article on a “Muslim-friendly alternative” to Web searching that filters haram content.

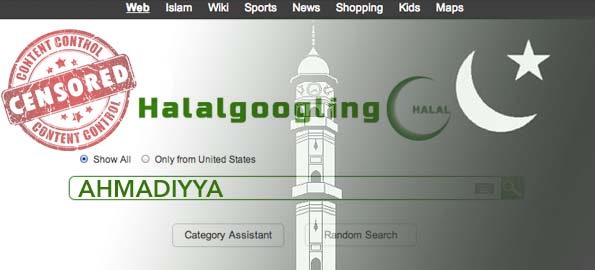

Intrigued, I clicked and read on: functions much like Google or Bing, but with a built-in “advanced special filtering system” that blocks content deemed haram or forbidden in Islam.

According to its web site Halalgoogling aims to be the number one search engine in the Muslim community: “Everyone has the right to enjoy the possibilities that the internet offers, to learn or to use it for work, to share the fruits of scientific achievements, different literature, technical information, to trade products or offer different services etc. However, we have the right to preserve our faith, our moral and the interest of our brothers and sister worldwide. We are here to ensure that such content is not contrary to the principles of Islamic religion.”

Halalgoogling (not to be confused with Halal Google) is a relatively new project and can be easily accessed by any Internet user atwww.halalgoogling.com. It is still difficult to estimate how widespread the use of this “sin-free” search engine is, though its Facebook page has gathered over eleven thousand followers, and besides Al Jazeera, has attracted coverage in various other media outlets with international reach, such as The Huffington Post, and the International Business Times among others.

Its “special filtering system” excludes forbidden sites as well as haram content from search results “such as pornography, nudity, gay, lesbian, bisexual, gambling, anti-Islamic content or anything else that is haram according to the Islamic law.”

The creators appear to be open to hearing from the Muslim community about content that might have escaped the haram filter, and they also offer a disclaimer explaining that despite best efforts to make the service as secure as possible, “we apologize any unintentional mistake that we might have made or could make in the future.”

Perhaps the creators are acknowledging that fail-safe censorship is not possible in the Muslim community, which like other faith communities, is instrinsically diverse. Naturally, Muslims have different preferences in approaching faith matters; while some will find the project beneficial, others will find it unnecessary. As a Muslim woman, I find this project in its current state absolutely unacceptable.

For example, according to Halalgoogling, the followers of Ahmadiyya Islam — a group of living Muslims — is, in fact, haram.

The Ahmadiyya are a historically oppressed Islamic reformist movement, which traces its roots to India in 1889 where it was founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (considered to be the promised Messiah and the Mahdi by the followers of the sect).

They believe that their spiritual leader was sent by God as a divine guide with the mission of ending bloodshed and immorality and reviving peaceful and loving Islam. Their message is: “Love for All, Hatred for None.”

Over the decades, the leadership of Ahmadiyya Islam has rejected violent revenge seeking in response to persecution, and continues to promote the bloodless, intellectual “jihad of the pen” and “jihad of the heart” as a way of defying prejudice.

Over time, the message of Ahmadiyya Islam has reached most corners of the world. The movement has its branches in more than 200 countries, and its membership exceeds tens of millions, the official website states. Its headquarters are located in London, where the Ahmadi leadership relocated from Pakistan following the anti-Ahmadiyya Ordinance XX of 1984. (A map demonstrating the establishment of the global Ahmadiyya Muslim Community over time can be found here.)

Mahmood Mosque at the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community headquarters in Kababir, Haifa, Israel. photo by Anastasia Karklina

Denounced by “mainstream” Islam and accused of fallacy, Ahmadi Muslims have faced institutional discrimination and hate crimes particularly in Pakistan, but also in Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Malaysia, Indonesia, etc.

So to me it comes as no surprise that Halalgoogling is a Pakistani project, a country where Ahmadi Muslims have faced ongoing persecution and prosecution for blasphemy, and where it’s a crime to be a follower of Ahmadiyya Islam.

Yet, one does not have to be a follower of this sect to understand that there is something inherently wrong with a project that does not allow access to official web pages of persecuted communities.

While the search engine does permit the Halalgoogling of a number of articles on the persecution of Ahmadis, it does not allow access to official websites (with few exceptions) set up by the Ahmadi leadership to educate the public on their vision of Islam.

A technical glitch? Likely not.

The Halalgoogling search engine enables the filter to display posts and forum discussions that call Ahmadiyya Islam a “fraud” or a “cult,” and their teachings the “words of Satan,” (easily accessible to Muslims on the Web) yet prevents direct access to information on MuslimsForPeace.org,PersecutionofAhmadis.org, or The Ahmadiyya Times. The owners ofHalalgoogling did not respond to a submitted question requesting their opinion on the subject matter.

As someone who cares about justice (and Islam instructs me to do exactly that), my studies have led me to believe that throughout world history — unjust and oppressive — the voice of reason often belongs to the oppressed.

In a 1994 interview, Chinua Achebe, a renowned Nigerian author, stated, “There is that great proverb — that until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

The Halalgoogling censorship of the official Ahmadi websites writes a “history of the hunt,” not that of the experience of the lions.

By erasing the Ahmadi-written narrative out of the complex record of contemporary Islamic realities, and avoiding the need to address serious questions of intolerance that persist in the practice of Islam, even if the persecutors are in the minority, we unknowingly glorify those who choose to sideline Ahmadis — when we as Muslims should be instead utterly ashamed of such prejudice, no matter what personal opinion on Ahmadi theological interpretations one holds.

The Halalgoogling project claims it is designed to “respect the Muslim Culture.” If there is anything like “Muslim culture” in existence at all, I have always thought that it would be one that reflects the message of the Islamic faith — that of respect for the humanity of others.

I am outraged at how western Islamophobia leads to racialization and criminalization of Muslims into a dangerous class to be feared, yet, I am left equally infuriated when some Muslim believers make it acceptable to exhibit the same kind of behavior towards others, and by extension of these censorship practices, effectively branding the oppression of minority groups as “permissible” in Islam.

Mosque at Ahmadiyya Muslim Mission’s headquarters in Accra, Ghana. photo by Anastasia Karklina.

Over the last three months, I conducted a research project on Ahmadiyya Islam, and, with generous support from Duke University, visited two Ahmadi communities, in Accra, Ghana, and Haifa, Israel.

I was particularly interested in exploring how Islamic non-violence informs the way Ahmadi Muslims negotiate their religious beliefs to navigate through conflict, particularly when non-Ahmadi believers in their immediate environments could potentially vilify the legitimacy of their identity.

I engaged in conversations with community leaders and members about tolerance and peaceful conflict resolution, and my interactions with members of both communities were marked by kindness and warmth. I could sense a sincere willingness to engage in dialogue with other believers, whether Muslim or not, and non-believers alike, and a strong dedication to the “Love For All, Hatred For None” advocacy that Ahmadis hope to spread through intellectual and informed dialogue.

While I am not an expert in religious specifics of the Ahmadi faith, I left in agreement with what Ahmadi Muslims have told me about themselves – that the ultimate message of their advocacy promotes Islamic values at its very core. In my mind, at the end of the day, it is the dignified treatment of others, and especially those suffering at hands of injustice, that serves as an overarching imperative to being a better Muslim.

As far as Halalgoogling goes, we should refuse to box ourselves in the intellectually stifling narrow-mindness of such “halal versus haram” discourse, particularly when it denies people the right to tell the story of their struggle in their own words.

Ultimately Halalgoogling is a small-scale project that, as of now, will likely remain in limited use among the estimated 1.7 billion Muslims worldwide. However, it is important to recognize it as an unsettling example, symptomatic of a much larger delinquency on our part.

There is no doubt that the beliefs of Ahmadi Muslims will contradict what many non-Ahmadi Muslims believe. We must however distinguish these theological disagreements from the treatment of a minority group that is both unjust and fundamentally un-Islamic.

Whether such treatment manifests itself in violent persecution, discriminatory policies or the denial of their right to self-representation, our complicity in one or all of the above cannot be possibly excused in the name of Islam. When we urge others to recognize and stand for Islamic values of justice and humane treatment of others, we also need to walk that talk. Scholarly contentions are secondary to these lived Islamic truths.

As long as blissful ignorance remains the status quo for our complicity with intolerance in the name of Islam, I will stick to my usual Web search practices. Silencing of the persecuted is not on my “halal list” and will never be.