A fortnight ago, tens of thousands of members of the Ahmadi Muslim community gathered in the historic English market town of Alton. They were there for an annual conference. This year, the community was also marking the centenary of its presence in Britain. As far back as 1926, the Ahmadis established London’s first mosque.

In countries as diverse as Canada and South Africa, there are similar events that take place throughout the year. But the one country where Ahmadis aren’t allowed to gather is where the roots of their faith lie: Pakistan. “We haven’t been able to hold a peace conference in Pakistan for the past 30 years,” says Qasim Rashid, the author of The Wrong Kind of Muslim: An Untold Story of Persecution and Perseverance. “They are banned by the Pakistani government, citing the country’s blasphemy laws.”

Each year, the Ahmadi community puts in a request to hold an event and are always denied. And yet, a few days after the Alton event, a very different kind of gathering was allowed to take place in Pakistan. To mark the 39th anniversary of the passing of the second amendment of the Pakistani constitution, which declared Ahmadis non-Muslims, a coalition of anti-Ahmadi religious groups met at a vast conference of their own. The event, held in Lahore, was marked by incendiary speeches that called for further economic and social isolation of the Ahmadi community. Some speakers even hinted at violence.

Mufti Muneebur Rehman, a prominent cleric who heads a committee responsible for sighting the moon at the start and end of the holy month of Ramadan, likened Ahmadis to fifth columnists. He alleged that members of the Ahmadi community were involved in “suspicious activities” and ominously added that “serious measures” should be taken against them.

The days leading up to September 7th are a source of much dread for Pakistan’s Ahmadi community. This year, three members of the Ahmadi community were killed in Karachi. The volatile southern port city is the site of near-daily urban violence, including targeted killings, but members of the Ahmadi community aver that all three men were killed because of their faith and not for political reasons.

On August 21st, Zahood Ahmad Kayani – a 40 year old resident of Karachi – was gunned down outside his house by two unidentified motorcyclists. Ten days later, an Ahmadi doctor was murdered in his clinic. The attackers had pretended to be patients, before opening fire on Dr. Syed Tahir Ahmad as he was seeing them. And just three days before the September 7th conference, another Ahmadi man who shot dead in Karachi.

In earlier years, a famed Pakistani televangelist once appeared on television to declare that Ahmadis were “wajib-ul-qatl” or “liable to be killed”. A few days after his remarks were aired, two Ahmadis were killed in Sindh province. The same televangelist was at the anti-Ahmadi conference in Lahore this year. When it was his turn to speak, he defended Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, which Ahmadis and other religious minorities blame for being used as a coercive tool against them.

Other speakers invoked chilling rhetoric that, in some ways, is familiar to religious minorities who have suffered persecution around the world. The Ahmadis were denounced as “stooges of the West,” by one speaker. Pir Muhibullah Noori, another speaker from the sufi-leaning traditions of the country, reportedly said Ahmadis should be “banished” from Pakistan.

Even more worryingly, a former judge, Mian Nazeer Akhtar, was reported by the Express Tribune newspaper as saying that the “time for speeches against Ahmadis was over and it was time to do something practical”. His suggestion: “[E]veryone should play their role against Ahmadis to tighten the noose around them”.

Even more worryingly, a former judge, Mian Nazeer Akhtar, was reported by the Express Tribune newspaper as saying that the “time for speeches against Ahmadis was over and it was time to do something practical”. His suggestion: “[E]veryone should play their role against Ahmadis to tighten the noose around them”.

On the same day, a separate anti-Ahmadi conference was also held in the Punjabi town of Rabwah, where the Ahmadi community is headquartered in Pakistan. It is also the only town in Pakistan where Ahmadis constitute a majority. “They used loudspeakers,” says Rashid, referring to the conference’s organisers. “There were calls for boycott and murder that terrified the local community.” In Rabwah, as elsewhere in the country, while their tormentors were making themselves menacingly visible, Ahmadis were advised to remain inside their homes until the anniversary passed.

Few Ahmadis are surprised by the rhetoric. It has become depressingly familiar to them, especially in recent years, as the violence against the religious minority has escalated. In May 2010, nearly 100 members of Lahore’s Ahmadi community were killed in terrorist attacks on two of their mosques in the eastern city. And between January 2012 and June 2013, the sect has faced 54 different attacks that led to the deaths of 22 members.

“The persecution is increasing,” says Rashid, who is a spokesperson for the Ahmadi community in the U.S. “In the last 29 years, since Gen. Zia-ul-Haq introduced anti-Ahmadi laws, 237 Ahmadis have been killed, and not a single arrest has taken place.”

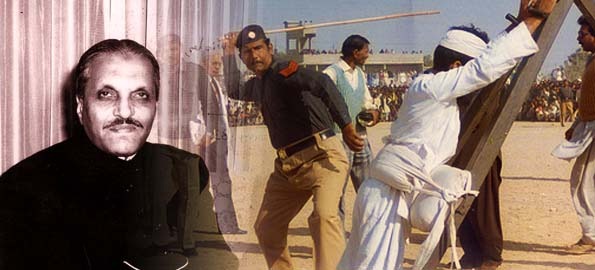

One of the grim ironies for Pakistan’s Ahmadi community is that laws discriminating against them were introduced by both a populist elected leader and a military dictator. September 7th marks the anniversary of the day in 1974 when the Pakistan People’s Party government led by then Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto introduced a constitutional amendment that was overwhelmingly passed to declare that Ahmadis are non-Muslims.

Bhutto was later overthrown in a coup and hanged by former military ruler Gen. Zia-ul-Haq. A few years after vaulting to power, Gen. Zia introduced a slew of fresh laws that made life even more difficult for Pakistan’s Ahmadis, sparking a rise in violence against the community that continues to this day.

As many Ahmadis point out, it wasn’t always this way. Pakistan’s founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah appointed an Ahmadi, Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, as his first foreign minister – Khan also happened the author of the declaration that first made a demand for a separate Muslim homeland in South Asia. (Another prominent Ahmadi whose name has been obscured is the country’s only Nobel laureate, Abdus Salam, the famed physicist.)

But as Jinnah’s vision for a tolerant and pluralistic Pakistan has receded into the distance, antagonistic views towards Ahmadis have become more mainstream. In November 2011, a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center found that two-thirds of all Pakistani Muslims regard Ahmadis as non-Muslim. A mere 7% said that they saw Ahmadis as fellow Muslims. The rest said they weren’t sure or didn’t express an opinion.

At the moment, the biggest concern for the Ahmadi community, says Rashid, is being effectively not allowed to vote. “Ahmadis are the only demographic that has disenfranchised from the electorate,” he says. To be able to vote, Ahmadis have to declare themselves non-Muslims. “Either you declare yourself a kafir (infidel), which Ahmadis are not allowed to do,” says Rashid, “or declare Mirza Ghulam Ahmad a kafir.”

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad was the founder of the Ahmadi community in 19th century India. Followers of the Ahmadi faith variously regard him as a reformer, a latter-day messiah, or a prophet. Orthodox schools of Islam, both Sunni and Shia, say that Muhammad was the final prophet. They regard any claims to prophethood after him as a grave heresy. Extremists say that heresy is punishable by death – one of the sources of the violence against Ahmadis and other heterodox religious communities.

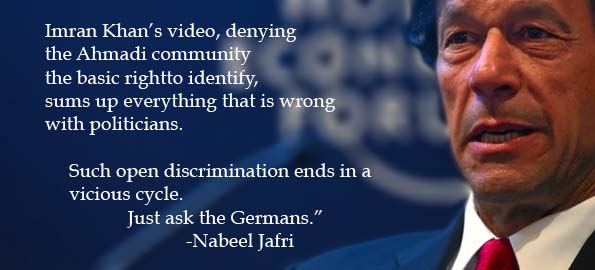

Although Ahmadis were not allowed to vote during Pakistan’s general elections held in May this year, they still managed to become an election issue. A religious fundamentalist political party accused former cricket legend turned politician Imran Khan of being hostage to “the Ahmadi lobby”. The fundamentalists made the allegation knowing that it could prove electorally profitable for them among those voters with hostile views towards Ahmadis.

With no Ahmadi votes to court, Pakistani politicians see no benefits of defending the religious minority. Despite having promised earlier in the campaign to uphold the rights of all religious minorities in Pakistan, Khan felt compelled to respond to the charge. At an election rally, he declared that Ahmadis are non-Muslims, demonstrating how the invidious question, “Who is a real Muslim?” ends up further isolating religious minorities.

The Ahmadis are not alone in this. In the central Punjabi city of Jhang, virulently anti-Shia candidates secured tens of thousands of votes after whipping up a frenzy of sectarian hatred. The anti-Shia candidates were denied victory in every seat they stood for election – a small mercy for members of the Shia community who have seen hundreds from their sect slaughtered in vicious terrorist attacks this year.

Despite the enduring threats, violence and discrimination, members of the Ahmadi community still manage to sound sanguine. “There’s still optimism. We’re a spiritual community, so we trust in God,” says Rashid, the author and spokesperson. “Our leader has advised us to remain patient, to remain loyal citizens of Pakistan, and to support Pakistan.”

But at the same time, there is an understanding that it may be safer to relocate to a country where Ahmadis can both practice their faith and participate in civil life by voting in elections. “If the opportunity arises, in the interests of security and safety,” adds Rashid, “our leader has been supportive of making the move.” The next time a congregation of Ahmadis meets in the English countryside for a conference, their numbers may include more new arrivals from Pakistan.