The Times London, 1985: Meet the spiritual leader of 10 million whose life could be at risk.

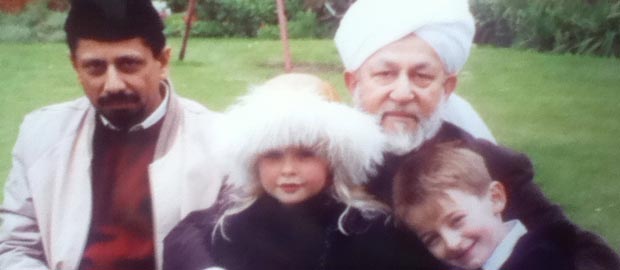

Few of the citizens of Wandsworth can be aware that living in their midst, in the humdrum surroundings of Gressenhall Road,.SW18, is the Fourth Successor of the Promised Messiah. But that is what more than 10 million Ahmadi Muslims scattered around the world believe, recognizing Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmed as the supreme head of their movement.

Of those 10 million, not more than about 10,000 live in Britain. The largest number – three or four million – live in Pakistan and so, until last year, did Mirza Tahir. He would much rather be there still, enjoying the mangoes from his gardens at Rabwah, in Punjab, which he boasts are the best in Pakistan. But circumstances have for the moment made that impossible.

The Ahmadis were enthusiastic supporters of the creation of Pakistan and provided its first foreign minister, Sir Muhammad. Zafullah Khan who died last Sunday at the age of 92. But from the early days of the state they came under attack from the mullahs (orthodox religious leaders) as being non-Muslims because they regarded their 1 9th-century founder, Mirza Tahir’s great-grandfather, as a prophet, whereas Muslim orthodoxy insists that Muhammad is the last of the-prophets.

In 1953 a campaign to have them declared a non-Muslim minority led to serious rioting in Punjab. In 1974, the Prime Minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, gave in to a second wave of agitation. The Ahmadis were officially declared non-Muslims and an affirmation of belief in the finality-of Muhammad’s ‘prophethood- was written into the oath of office of both president and prime minister.

Although thus excluded from high political office and from marrying other Muslims, the Ahmadis were left largely undisturbed as a community until April 26 1984, when after a further intensive campaign by mullahs carried ‘ on with some official encouragement, President Zia promulgated an ordinance forbidding them to call themselves Muslims or use any Islamic terminology to describe their buildings and activities. They were also forbidden to use the AZAN, or public call to prayer.

It was immediately after this that Mirza Tahir left Pakistan and came to London. The anti-Ahmadi campaign had included accusations that the movement had kidnapped a well-known mullah, and demanded that Mirza Tahir should be interrogated in connection with this crime. But he insists, he is not in.any sense a fugitive from justice.

“As far as. the government of, Pakistan is concerned, it has not levelled any accusation against me or initiated any inquiries against me, in spite of pressure from the mullahs.” The government, he says, had held a series of inquiries into the alleged kidnapping, each of which “reached a stage where it exonerated me and the community”, but each time the findings were kept secret and a new inquiry was set up.

This had been going on for 18 months before Mirza Tahir left Pakistan on April 26 last year. What made him-decide to leave, he says, was *not any allegation but- the’ ordinance of April 26″ -which “did not leave, any room for any head of the Ahmadi community to remain in Pakistan”

The Ahmadis firmly believe ththemselves to be Muslims – indeed the only true Muslims, recalled so the essence of Islam by the message of their, founder, Hazrat. Mirza Ghulam Ahmad.. This does not they say involve any denial of the Prophet Muhamrmad’s status as “Seal of the Prophets”,(Khatm al- Nabi’in), because Mirza Ghulam did not claim to bring a new ‘revelation of divine law which would replace or supersede the Koran, as the Koran itself is deemed to have superseded the law ‘of Moses and the gospel of Jesus Christ.

That being so, it is clearly impossible for the head of the Ahmadi community to discharge his duties without making any public reference to Islam. Yet, under the terms of the ordinance, anyone claiming publicly to be a Muslim is required to declare that he regards Mirza Ghulam as an impostor – something equally impossible for a conscientious Ahmadi to do. Mirza Tahir was thus obliged to leave Pakistan to continue discharging his duties as head of the community.

Not that he is a stranger to this country. He studied here in the 1950s at the,School of Oriental and African Studies. In this’ respect there is some similarity to the Ismaili community whose leader, the Aga Khan, studied at Harvard under the great British orientalist Sir Hamilton Gibb.

Not that he is a stranger to this country. He studied here in the 1950s at the,School of Oriental and African Studies. In this’ respect there is some similarity to the Ismaili community whose leader, the Aga Khan, studied at Harvard under the great British orientalist Sir Hamilton Gibb.

But Ahmadis stress that whereas Ismailis are a very wealthy community whose prosperity derives from commerce and which does not actively seek, converts, the Ahmadi community has relatively small economic resources – its most distinguished members being public servants such as diplomats or army officers but does seek actively to propagate its versions of Islam throughout the five continents.

Certainly the “London Mosque” in Gressenhall Street is a modest affair, without pretension to rival the glamour of the new Ismaili Centre in South Kensington. A larger centre for the Ahmadi community in Britain is now being built at Tilford, Surrcy, under-the name of “Islamabad” – which may seem provocative, but the Ahmadis were using it as a telegraphic address in 1924, long before the present capital of Pakistan, or indeed Pakistan itself, was even on the drawing board.

The irony is that in present-day Pakistan it is a crime even to describe any Ahmadi building as a ‘mosque”. Worse than that, a climate has been created in which mullahs can with impunity describe Ahmadis as enemies of Islam deserving death, and anyone who has a grudge against an individual Ahmadi can take action against him with little fear of legal sanction. Ten prominent Ahmadis have been murdered in Pakistan since April 1983, mostly in the province of Sindh, and attempts have been made on the lives of three others. In no case has the assailant been arrested.

Last month an anti-Ahmadi conference was held in London. Participants, speaking in Urdu, are said to have described assassination of Ahmadi leaders as a sure way to enter paradise. In a message, President Zia promised to “persevere in our effort to ensure that this cancer is exterminated”.

Mirza Tahir has not asked for asylum in Britain. He remains here temporarily – resisting appeals from the growing Ahmadi community in America (particularly among American blacks) for him to make his home there – because London provides not only religious freedom but also an ideal situation for contact with Pakistan and other countries. He firmly expects to return to Pakistan, hoping that ‘the ordinance will go overboard with the dictator himself’.