The largest mosque in Japan opened its doors on November 20 near the central Japanese city of Nagoya, heralding a new chapter in the East Asian nation’s relationship with Islam.

Islam has never made more than a marginal impact on Japan, although the history of Japanese relations with Muslims stretches back further than most people imagine, the Japanese included.

The first mosque in Japan, the Kobe Muslim Mosque, opened in October 1935 and remains a centre for prayer more than 80 years later. Several dozen other mosques have since opened around the country, serving as community centres for a Muslim population numbering in the tens of thousands.

The first Ahmadi Muslim missionary arrived in Japan in the same year – 1935 – but it is only now that this minority community has had the resources to build its own centre, the Bait ul-Ahad Mosque. They have done so on a grand scale, building the Japan’s biggest mosque with a capacity in its main chamber for 500 people to be at prayer.

The opening ceremonies were attended by a range of guests, including a Japanese politician and local city officials, as well as leaders of the Ahmadi Muslim community from around the world. At the head of the guest list was Caliph Mirza Masroor Ahmad, the supreme leader of the 20 million-strong global Ahmadi community.

“This is a milestone of our progress,” Caliph Ahmad told Al Jazeera. “If this mosque is preaching the message of love, peace, and harmony, naturally people will be attracted to it.”

The main distinction between the minority Ahmadi Muslim community and the majority of Muslims is the former’s belief that Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835-1908) was the foretold messiah and mahdi who brought his followers back to the spirit of the original Muslim community at the time of the Prophet Muhammad.

Many in the majority Muslim community dispute Ahmadi views on the caliphate and on continuing revelation in the contemporary age and do not regard their teachings to be part of orthodox Islam.

Many in the majority Muslim community dispute Ahmadi views on the caliphate and on continuing revelation in the contemporary age and do not regard their teachings to be part of orthodox Islam.

According to Muhammad Ismatullah, the leader of the Tokyo-based community, Ahmadis in Japan number fewer than 300 people, and are mostly Pakistanis, with perhaps 10 percent who are ethnic Japanese.

The largest portion of the Ahmadi community lives in the vicinity of the industrial city of Nagoya. The man responsible for this fact, Ataul Mujeeb Rashed, was in attendance at the opening of the Bait ul-Ahad Mosque.

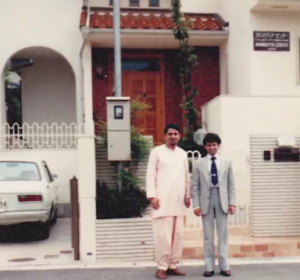

Today, Rashed is, among other things, the imam of the Fazl Mosque in south London, but from 1975 to 1983 he was an Ahmadi missionary to Japan.

In the late 1970s, he could often be found handing out religious fliers at the Hachiko exit of Tokyo’s Shibuya Station.

The Ahmadi caliph at that time had decided that it would be a more effective strategy to spread Islam by starting not in the capital cities of the countries where missionary activities were ongoing but elsewhere.

The Ahmadi caliph at that time had decided that it would be a more effective strategy to spread Islam by starting not in the capital cities of the countries where missionary activities were ongoing but elsewhere.

In the case of Japan, it was Rashed who recommended Nagoya as the base from which to begin.

“I proposed Nagoya firstly because it was the fourth-largest city in Japan … and secondly [because] it is, geographically speaking, right in the middle of Japan,” Rashed explains.

The caliph accepted Rashed’s proposal and thereafter Nagoya became the main stage for Ahmadi activities in Japan.

In the final years of his mission, Rashed even decorated a white Toyota car with religious slogans written in Arabic, English, and Japanese, and drove through rural towns preaching the faith over a loudspeaker system that he had fixed to the car roof.

While these efforts did not result in mass conversions, the ‘Toyota in the Service of Islam’ was the focus of a great deal of curiosity wherever it passed.

While these efforts did not result in mass conversions, the ‘Toyota in the Service of Islam’ was the focus of a great deal of curiosity wherever it passed.

The new Bait ul-Ahad Mosque promises to serve as the key base for the Ahmadi community of Japan, but its capacity – 500 worshippers – is far greater than the number of Ahmadis in the country.

“Certainly a building half this size would be sufficient for the Ahmadis residing in Japan,” said Masayuki Akutsu, a researcher at The University of Tokyo. “However, this mosque has been created not solely for their religious activities; rather, it is also for their social interactions with the broader Japanese society.”

It remains doubtful that Islam – whether in the Ahmadi form or otherwise – will make significant inroads in Japan.

But in offering a direct, experiential counterpoint to the negative, fear-inducing images of Islam often conveyed, such initiatives may help in building bridges and breaking down divisions.