Rabwah, Pakistan – Seeing her lying in her hospital bed, it’s difficult to tell what Mubashara Jarra has been through. Outwardly, she appears fine. No intravenous tubes snaking into her body, and no bandages covering up her wounds.

“I’m feeling much better,” she says, in a low voice.

It is, perhaps, only her vacant eyes that betray her ordeal. Jarra, 32, was trapped in a room, along with many of her family members, in her home in the Pakistani city of Gujranwala, as an angry mob burned down her neighbourhood on July 27. She saw her nieces – Hira Tabussum, 7, and seven-month-old Kainat – and mother, Bushra Bibi, 55, die of smoke inhalation, as she, her brother and his children struggled to stay alive.

Jarra barely survived, but her unborn child – she was seven-months pregnant – was stillborn at the hospital where she received treatment following the attack.

Their crime? Being Ahmadi in Pakistan.

‘Institutionalised persecution’

Ahmadi, or Ahmadiyya, are a minority sect who identify themselves as Muslims and follow the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad and the Quran. They believe that the founder of their faith, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who was born in the Punjab town of Qadian in 1835, was a messiah and prophet.

There are estimated to be between 600,000 and 700,000 Ahmadis in Pakistan, with worldwide numbers of several million more. Most reside in South Asia, but there are large diaspora communities in Europe, and there are also indigenous Ahmadi communities in parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

Since 1974, Ahmadis have been declared “non-Muslim” under Pakistani law, after a constitutional amendment was passed under the government of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

That amendment allowed Islamist military ruler Zia-ul-Haq, who succeeded Bhutto, to further restrict Ahmadis’ freedom to practise their religion in Pakistan through a 1984 ordinance that outlaws “posing as Muslims”.

The law imposes three-year jail terms on Ahmadis “who directly or indirectly, poses himself as a Muslim, or calls, or refers to, his faith as Islam, or preaches or propagates his faith, or invites others to accept his faith, by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representations, or in any manner whatsoever outrages the religious feelings of Muslims”.

It also makes it illegal for Ahmadis to refer to their places of worship as “mosques”, or their calls to prayer as “azaan”, in addition to other restrictions.

The 1984 law opened the door for an increase in attacks on the community by mobs and anti-Ahmadi groups. Since 1984, 245 Ahmadis have been killed in such attacks, while another 205 have been assaulted, according to the community’s data on such attacks.

So far in 2014 alone, 13 Ahmadis have been killed for practising their faith – most in targeted attacks on individuals – and another 12 have been assaulted.

“This is all happening because of a law that has institutionalised the persecution of Ahmadis,” says Mujib-ur-Rehman, an advocate at the Supreme Court and a senior member of the Ahmadi community. “This is the kind of legal framework which sanctions the persecution of Ahmadis, and it is done under the cover of law. This does not happen to any other community [in Pakistan].”

Pakistan has been racked by attacks related to the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and its affiliates for years, but sectarian violence, especially targeting Shia Muslims, has also been on the rise in recent years. More than 3,600 people have been killed in sectarian violence since 2002, with 722 of those being killed in 2013 alone.

Ahmadi community leaders, however, say that the persecution of their sect is different, in that it is sanctioned by law.

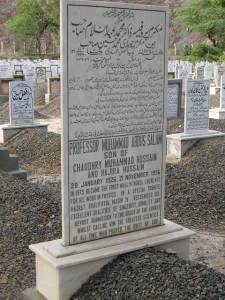

“The discrimination against an Ahmadi begins at birth, and even after death when they are being buried, it continues,” says Saleemuddin, the community’s spokesperson in Pakistan, explaining how cases have been lodged against Ahmadis for saying the ‘azaan’ into the ears of newborns (a traditional Muslim practice), and how their gravestones have been defaced for carrying Quranic verses.

The law is also broad and open to interpretation, critics say. Cases have been lodged against Ahmadi Muslims for everything from having minarets on their mosques to reading the Quran, from having Quranic verses printed on wedding invitations to praising the Prophet Muhammad, according to police reports seen by Al Jazeera.

The law is also broad and open to interpretation, critics say. Cases have been lodged against Ahmadi Muslims for everything from having minarets on their mosques to reading the Quran, from having Quranic verses printed on wedding invitations to praising the Prophet Muhammad, according to police reports seen by Al Jazeera.

“[Outraging the sentiments of Muslims] is something that I am not doing, it is something that [the other person] is feeling. Now if I am sitting at home and reading the Quran, your sentiments are outraged. If I am watching a TV programme, your sentiments are outraged,” says Rehman. “Using this as a basis, anyone can do anything […] I don’t even know what the criminal actions are!”

Killing ‘a religious obligation’

Anti-Ahmadi groups, meanwhile, continue to be free to spread their message and to organise rallies where they call the killing of Ahmadis a “religious obligation”.

One such gathering was held several days after the incident in Gujranwala, where a local cleric demanded that those arrested in connection with the arson and killings be released immediately.

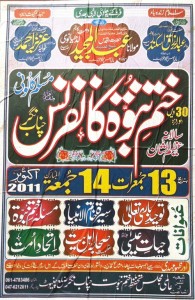

Most prominent among these groups is Khatm-e-Nabuwat (Finality of Prophethood), which organises regular rallies and conferences against the Ahmadi community, terming them heretics for not accepting the finality of the prophethood of Muhammad.

Most prominent among these groups is Khatm-e-Nabuwat (Finality of Prophethood), which organises regular rallies and conferences against the Ahmadi community, terming them heretics for not accepting the finality of the prophethood of Muhammad.

The group also distributes a number of pamphlets, several of which call upon followers to consider killing Ahmadis a religious obligation.

“Awaken your conscience and become a mujahid [of the organisation] and kill [Ahmadis] to attain the status of a martyr,” reads one pamphlet distributed in the city of Multan, in Punjab province.

Another, issued in the town of Qamber in Sindh, says that “under the Shariah of Muhammad it is an obligation to kill [Ahmadis]”.

Despite several complaints, community leaders say action is seldom taken against such groups under Pakistan’s existing hate speech laws.

Conversely, applications moved by Khatm-e-Nabuwat to police and courts have seen the community ordered to restrict their practises, according to police reports obtained by Al Jazeera.

In several instances, the community was ordered to take down lighting and bunting displays during religious celebrations, for example, according to those reports.

‘In their eyes, we are weak’

Rameeza*, 39, says that the police, courts and even the public seldom support Ahmadis, even after attacks on the community.

Rameeza’s husband, Rizwan*, was killed on August 6, 2009, in a targeted attack on their Multan home while she and their three children watched on.

Rizwan’s killers, who have since been captured and are undergoing trial, said that he was targeted because he played a prominent role in the local Ahmadi community’s activities.

“I took [his wounded body] to the gate of the house,” she told Al Jazeera, of the moments after the shooting. “I asked people to bring a car or to call the rescue services. No one was prepared to help me. There was a rickshaw parked in the street, even he was not prepared to go for help.”

Rameeza said that she has faced constant threats during the course of the trial, and that mobs would often form outside the courthouse on the days she and her family members were testifying.

Rameeza said that she has faced constant threats during the course of the trial, and that mobs would often form outside the courthouse on the days she and her family members were testifying.

Fearing another attack, she has since fled to Rabwah, a small town of about 60,000 people that serves as the community’s headquarters in Pakistan.

Rameeza and her three children are just one of the more than 100 families who are currently taking refuge in Rabwah following attacks on them, according to community leaders. Most fled to Rabwah after the twin attacks on Ahmadi mosques in the city of Lahore in 2010, which killed 94 people.

Saleemuddin, the community’s spokesperson for the last eight years, says that police have often approached the community to “accept” the demands of those who would persecute them, rather than charging those people with hate speech.

“In their eyes, we are weak. They try to pressure us as much as possible [after attacks]. They know that we are not going to take out protest rallies or marches after any attack, so for them it’s very easy to call the local community and tell them that local Maulvis [religious scolars] have too much power, and that the Ahmadis must accept the situation. That is their usual behaviour,” he said.

Zohra Yusuf, the chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), says that the police are “deeply entrenched” in the persecution of Ahmadis.

“There is a reticence to file [cases] or to pursue killers by the police,” she told Al Jazeera. “There really is a total absence of justice when it comes to the Ahmadi community.”

Meanwhile, Muhammad Boota, Mubashara’s brother, has filed a legal case against the mob and the instigators of the July 27 attack on his home, and those of seven others. Community leaders, however, say they do not expect much to come of it.

The police, they say, have asked the community to hand over a boy, Aamer*, whose Facebook posts allegedly sparked the violence.

“Will his family be ready to hand over their son to the same police in front of whom a mob killed other members of their family?” asks Saleemuddin, adding that the family and all other Ahmadis from the Gujranwala have gone into hiding, where the community is trying to protect them.

“But what protection can we give them? They have fled from [Gujranwala], but what had to happen, it has happened. The three people died, their homes and property were burned. What can happen more than this?”

*Some names have been changed at the request of interviewees, to protect their identities in the event of reprisal attacks.

Follow Asad Hashim in Twitter: @AsadHashim