Rabwah, PAKISTAN – This must be the only newspaper office in all of Pakistan that is alive and buzzing at 9:00am. While the country’s other sub-editors, reporters and publishers are still sleeping off last night’s print deadline, these journalists are already hard at work, drafting the next edition of Pakistan’s oldest continuously published daily newspaper.

Al-Fazl, the community newspaper of the Ahmadi Muslim sect, was first published in 1913, in the town of Qadian in what is today Indian Punjab. With the partition of the subcontinent in 1947, the Ahmadi community largely migrated to newly formed Pakistan, establishing the town of Rabwah in 1948. They brought al-Fazl with them, and it has been published from Rabwah ever since.

Ahmadis, also known as Ahmadiyya, are a sect that identifies themselves as Muslims and follows the teachings of the Quran and the Prophet Muhammad. They also believe that the founder of their faith, Ghulam Mirza Ahmad, was the messiah and a prophet, a point on which many hardline Pakistani clerics have demanded (successfully) that they be legally declared “non-Muslim”.

There are around 700,000 Ahmadis currently resident in Pakistan, living under restrictive laws that bar them from openly practicing their faith, put in place first under a democratic government in 1974 and later strengthened by military dictator Zia-ul-Haq in 1984.

Under an ordinance passed by Zia in 1984, additions were made to Pakistan’s Penal Code to punish Ahmadi’s who “pose as Muslims”.

In full, the law states:

“Any person of the Qadiani group or the Lahori group (who call themselves ‘Ahmadis’ […]), who, directly or indirectly poses himself as a Muslim, or calls, or refers to, his faith as Islam, or preaches or propagates his faith, or invites others to accept his faith, by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representations, or in any manner whatsoever outrages the religious feelings of Muslims, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years and shall also be liable to fine.”

In addition, Ahmadis were barred, on pain of three years imprisonment and a fine, from using the words “azan” or “mosque” when referring to their religious practices, as well as seven other terms (mostly epithets for the Prophet Muhammad, his family and his companions).

For the editors of al-Fazl, these laws, in addition to declaring their religious practices illegal, also make their work particularly challenging.

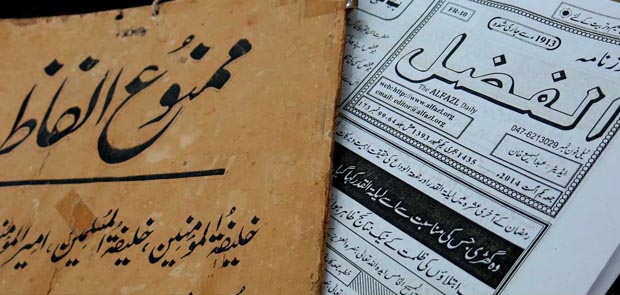

“We have to look for the regular grammar and spelling mistakes in the copy,” says Faiz*, 44, an assistant editor at al-Fazl since 2000, “but I also have to carefully go through every line to make sure that none of these forbidden words goes through!

“The result is that sometimes we even let a few [grammar] mistakes go, because we spend so much time looking for these words,” he says, pointing to a board with the list of “forbidden words” that is his constant companion at the copy desk.

As is often the case with restrictions on the press, the editors have found a way around these restrictions: you’ll find al-Fazl’s stories dotted with parenthetical dashes [“(-)”], blanks where certain forbidden words (such as “Muslim”) were meant to be.

“The readers of al-Fazl must be the most canny in the world,” jokes Asif*, a volunteer in the community who was showing me around Rabwah. “By now they know even without thinking what word is meant to fit into each dash.”

Ali*, another community activist, gives him a sharp look, at this.

“This not the kind of intelligence that we’d like to have,” he adds, wryly.

‘This is our sacrifice’

All the care the editors take, however, doesn’t seem to be enough. Since the 1984 ordinance, there have been more than 90 legal cases against the newspaper, its printers, editors and publishers, all lodged under the allegation that the paper is proselytizing, Abdul Sami Khan, the editor-in-chief, told me. It has also been shut down for short stints several times in that period.

Khan has been the editor for the last 16 years, and has himself faced several cases in court. It is the latest one, which is ongoing, that keeps him from being able to work from his own office, for fear of arrest.

Even the press, where other periodicals and books are also published, is constantly under threat of being shut down, he says, adding that non-Ahmadis who have provided printing services to the community in the past have also been jailed on occasion.

“And then of course there is always the threat that there could be a bomb blast,” he adds, nonchalantly, almost as an afterthought.

Threats to life aside, there are other issues, too. While the newspaper is not banned by the Pakistani authorities, the Pakistan Post unilaterally decided two years ago to stop delivering the newspaper to its roughly 8,000 subscribers.

Threats to life aside, there are other issues, too. While the newspaper is not banned by the Pakistani authorities, the Pakistan Post unilaterally decided two years ago to stop delivering the newspaper to its roughly 8,000 subscribers.

Online, where Sami says most of al-Fazl’s readers access the newspaper, the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) has taken the equivalent step, periodically blocking the newspaper’s website.

Hawkers who have carried the newspaper have also been charged under Pakistan’s Ahmadi-specific blasphemy laws – the latest case occurring last year, when six people, including three hawkers were charged in Lahore.

In contrast, the website and publications of the Khatm-e-Nabuwwat organisation (KeN), an anti-Ahmadi group that calls the killing of Ahmadis “a religious obligation”, continues to be accessible. KeN, which has registered numerous cases against Ahmadis for practicing their faith and motivated attacks on individuals, will also be holding its annual conference, wherein the “sins” of the Ahmadis will be enumerated, on August 23, on a government-owned property in the town of Jarranwala.

Khan takes a philosophical approach to the threats.

“There is constantly a sword hanging over our heads. Our position is that our community has been chosen by God, so what is happening to us is the same thing that has happened to other communities that were chosen,” he tells me, just before we end our meeting.

“We are taxpayers, and we do not take out rallies or protests [against this persecution], but we are shut out of the Pakistani mainstream entirely. We have no representatives in the local government, or provincial or national assemblies.

“They tell us that we have to deny that we are Muslims to vote. So this is our sacrifice.”

*The names of some interview subjects have been changed, at their request, for security reasons.

Fund Asad Hasim’s work – Follow Asad Hashim on Twitter: @AsadHashim