It was a relatively cool evening in Rabwah, a few days ago. I was there on an invitation to attend an enthralling seminar on “The shroud of Turin”, held in a state of the art Auditorium of Nusrat Jehan College for girls.

My host was the exuberant Faateh Bajwa, deputy director of Ahmadiyya community’s central education Department, referred to as Nazarat Taleem. After the seminar, I was shown around, and I must confess I was dumbstruck by the sprawling campus, quality of facilities and the dedication of somewhat fledgling but highly motivated staff at the college.

My host was the exuberant Faateh Bajwa, deputy director of Ahmadiyya community’s central education Department, referred to as Nazarat Taleem. After the seminar, I was shown around, and I must confess I was dumbstruck by the sprawling campus, quality of facilities and the dedication of somewhat fledgling but highly motivated staff at the college.

Nusrat Jehan means “universal victory”. Probably, it is the name of the college that has been talismanic in helping it achieve success against all odds. As Ahmadiyya community’s flagship institute, Nusrat Jehan college in Rabwah, not only caters to girls but a separate boys campus goes by the same name as well.

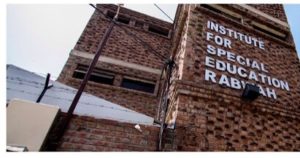

For a boys college to borrow its name from a woman is unprecedented in a country where male chauvinism and patriarchy have been a norm. Associated with education sector myself, I took a keen interest in visiting various institutes operating under the auspices of Nazarat Taleem.Out of their 13 non-profit schools in the town, boasting a strength of over 9,000 students, the one that moved me was the Institute for special education, a school for kids with special needs.

The facility was small, but the teaching staff had big hearts and broad smiles on their faces.

Currently, 95 Students with Cerebral palsy, Epilepsy, Physical handicap, Intellectual and hearing impairment and Down’s syndrome are given quality treatment regardless of caste, creed or religious.

Currently, 95 Students with Cerebral palsy, Epilepsy, Physical handicap, Intellectual and hearing impairment and Down’s syndrome are given quality treatment regardless of caste, creed or religious.

As I entered, I noticed that most of the students were going outside for their routine sporting activities. The dedicated principal, Amtul Jameel Sahiba, was optimistic that one day her kids would partake in Special Olympics even though no official from Pakistan’s Special Olympics committee had bothered to visit the institute, despite her regular insistence.

This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to chilling indifference towards Ahmadis, as indicated by the tumultuous history.

The biggest jolt Ahmadiyya community faced in terms of education was the policy of nationalization of private institutions enforced under Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s regime in 1970’s.

The biggest jolt Ahmadiyya community faced in terms of education was the policy of nationalization of private institutions enforced under Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s regime in 1970’s.

Post Bhutto’s era, all educational institutions that were nationalized were acquired back by the real owners barring the Ahmadiyya community. Till date, the community is striving unsuccessfully to reclaim the three educational institutes that were nationalized. The famous of the lot was Taleem ul Islam (TI) college, Rabwah.

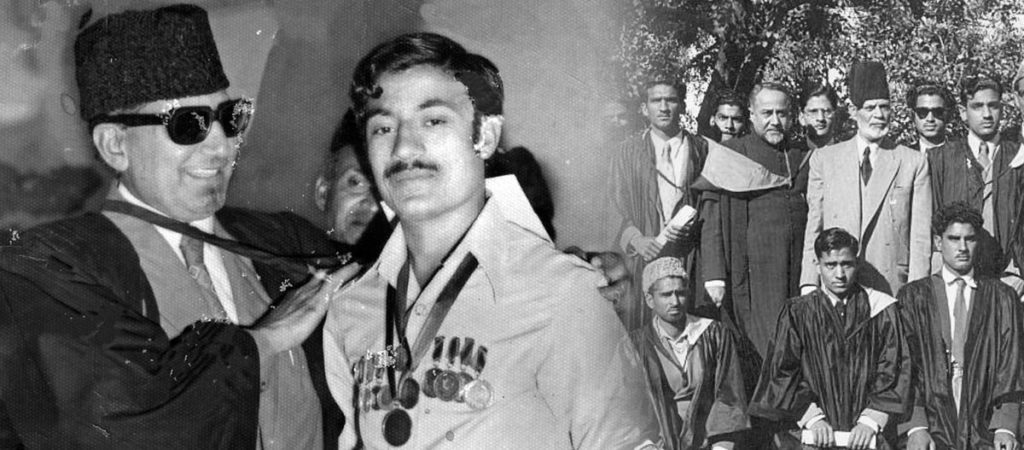

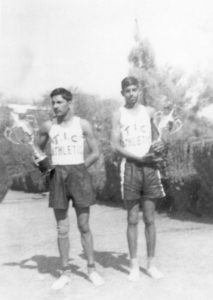

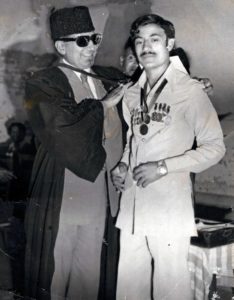

The close affinity of most Ahmadis with TI college, Rabwah can be gauged by the fact that either them or their acquaintances have been associated with the once coveted institute in one way or the other.

A few residents also highlighted the enviable debating culture at T.I. college that even gave Government college Lahore a run for its money during its heydays.

A few residents also highlighted the enviable debating culture at T.I. college that even gave Government college Lahore a run for its money during its heydays.

That robust culture died a long time back when the institution was nationalized by the state.

Fearing persecution under the draconian regime of Zia, who succeeded Bhutto, the community members kept their lips mum.

Putting it plainly, an educational apartheid was carried out, where the state chose populism over principles by usurping educational institutes run by the peaceful minority to assuage the Mullahs.

Putting it plainly, an educational apartheid was carried out, where the state chose populism over principles by usurping educational institutes run by the peaceful minority to assuage the Mullahs.

With their backs against the wall, top leadership of the community sat down to devise a cogent program to safeguard the future of Ahmadi students in adverse circumstances. In 1991, the initial fruit of their serious deliberation was reaped in the form of Nusrat Jehan academy, a school that caters to both boys and girls on separate campuses.

Ever since the scheme’s inception, there has been a multiplicity of facilities, institutions, and ideas despite limited resources.

The pivotal aspect of this model is that it breathes the essence of volunteerism and community work. It embraces with open arms dedicated educationists from all over Pakistan who are willing to chip in with their valuable contributions.

Most Ahmadis working in Nazarat Taleem are volunteers. Some have even left lucrative jobs at blue chip companies like ICI and Telenor to work in the remote town of Punjab. Mirza Fazal Ahmad sahib, the director of the department and a Charter Accountant by academic qualification, is no exception. He is investing all his energies and resources in building the system into a sustainable one.

Most Ahmadis working in Nazarat Taleem are volunteers. Some have even left lucrative jobs at blue chip companies like ICI and Telenor to work in the remote town of Punjab. Mirza Fazal Ahmad sahib, the director of the department and a Charter Accountant by academic qualification, is no exception. He is investing all his energies and resources in building the system into a sustainable one.

It was inspirational to see that low wages and limited resources have not let their shoulders drop; in fact, the positive vibes have been permeative and contagious.

Nazarat Taleem’s financial aid office operates on non-discrimination policy as well. On the list of those drawing stipends is a non-Ahmadi Baloch boy, who belongs to Ahl-e-Hadis sect. Once he contacted the relevant office for help, the department obliged by funding his undergraduate degree on humanitarian grounds.

It is even more remarkable that all funds are self-generated within the community and not a single penny is provided by the government.

Such a sustainable educational model evolved by the community is quite a rarity in a country which is grappling with educational woes with over 25 million children out of school according to the latest survey by Alif Ailan.

Perhaps Agha khan community is the only other minority in the country that has lead by example on this account. But unlike the Agha Khanis, Ahmadis had to deal with acrimonious circumstances on a consistent basis.

Perhaps Agha khan community is the only other minority in the country that has lead by example on this account. But unlike the Agha Khanis, Ahmadis had to deal with acrimonious circumstances on a consistent basis.

The 2010 terrorist attacks on two Ahmadi Mosques amplified the already prevalent anti-Ahmadi sentiments on campuses, a few notches.

Then in the year 2011, a new stipulation required all Ahmadi students appearing for Punjab board exam to identify them as “non-Muslims”. It was an unwanted clause that added insult to injury.

At that crucial juncture, Nazarat Taleem took a leap of faith and switched their student body to the Agha khan Board instead. With Time, the decision proved to be a blessing in disguise. As the cutting edge, Agha khan board curriculum had more to offer compared to Punjab board syllabus.

At that crucial juncture, Nazarat Taleem took a leap of faith and switched their student body to the Agha khan Board instead. With Time, the decision proved to be a blessing in disguise. As the cutting edge, Agha khan board curriculum had more to offer compared to Punjab board syllabus.

Under proper guidance and mentorship, numerous Ahmadi students around the country secure Top positions in board and university exams on a continuous basis and Nazarat Taleem magnanimously recognize all high achievers.

With Success as its hallmark, Nazarat Taleem has been instrumental in facilitating bright Ahmadi students into prestigious institutes like LUMS and IBA on full scholarship under the merit-based national outreach program every year.

But the stories of glaring injustices in our educational landscape seem to be present in every Ahmadi household.

Fateh shared that his own sister, along with other Ahmadi students, was rusticated from the Punjab medical college Faisalabad in 2012 merely on the account of being an Ahmadi . It all happened in broad daylight and sadly no action was taken.

Fateh shared that his own sister, along with other Ahmadi students, was rusticated from the Punjab medical college Faisalabad in 2012 merely on the account of being an Ahmadi . It all happened in broad daylight and sadly no action was taken.

Nazarat Taleem’s placement center came to their rescue and helped them secure berths in various universities across the globe and around Pakistan, where on campus atmosphere was not hostile.

As I reached the fag end of my two days sojourn, I was given another gracious invitation of an international medical conference to be held later this year.

Despite my non-medical background, I gleefully accepted it when the benevolent purpose of the conference was enunciated upon me.

Two years ago when doctor Mahdi Ali, a US-based Ahmadi cardiologist and an important member of Tahir Heart Hospital, was cold-bloodedly murdered in Rabwah, Nazarat Taleem bounced back and filled his void by initiating an international medical conference, where doctors especially cardiologists from all over the world participated with great oomph.

Two years ago when doctor Mahdi Ali, a US-based Ahmadi cardiologist and an important member of Tahir Heart Hospital, was cold-bloodedly murdered in Rabwah, Nazarat Taleem bounced back and filled his void by initiating an international medical conference, where doctors especially cardiologists from all over the world participated with great oomph.

With the second installment of the international medical conference around the corner and Doctor Abdus Salam research forum operating in full pelt, the future looks bright but the consequences of educational apartheid carried out by the state in the past and at present is what perturbs the beleaguered minority.