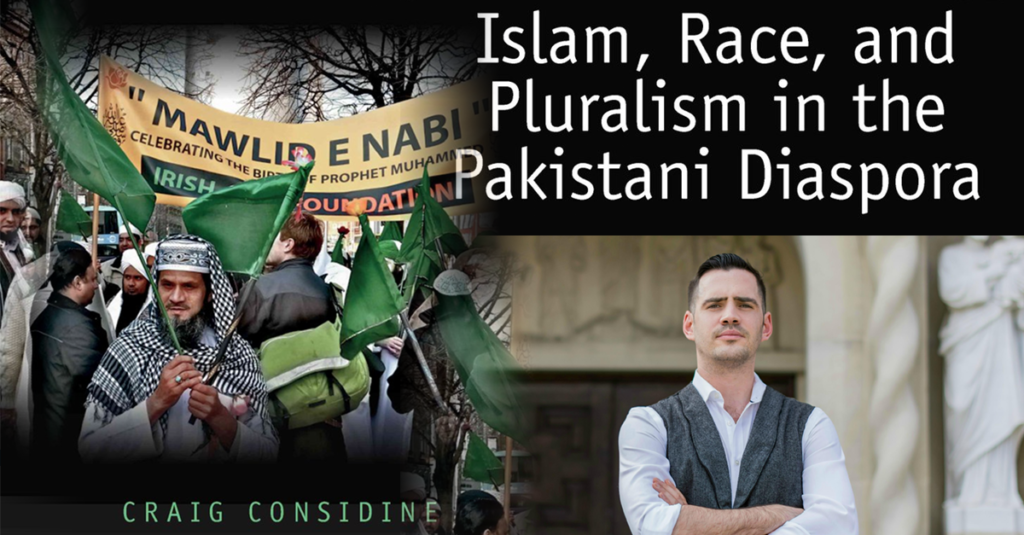

In his book, Islam, Race, and Pluralism in the Pakistani Diaspora, Dr. Craig Considine explores the experiences of several Pakistani American and Pakistani Irish men. He expertly unpacks these experiences while also being extra diligent in avoiding the notion of a singular diasporic identity and maintaining and furthering the heterogeneity present within the community. Further, these experiences are brilliantly contextualized through the compendious exploration of histories of Boston and Ireland, the settings of his research. Ultimately, the book puts an emphasis on the agency that Pakistani men in Boston and Ireland have over their response, and often resistance, to being marginalized.

Dr. Considine structures his research into 8 chapters. The first two chapters provide necessary background into his research as well as important theories that would be discussed later in the book and the last chapter provides possible solutions towards “fostering religious pluralism and interculturalism.” His interviews with Pakistani men are structured into the other five chapters, each focusing on a different theme including, but not limited to, the dichotomy of the “good” versus “bad” Muslim, and political issues such as terrorism. He also introduces the term “Pakphobia” which describes a fear of or apprehension towards Pakistani people in America and Ireland.

There are many issues Dr. Considine tackles within the book which naturally comes through from the multiplicity and pluralism present within the Pakistani community. A heavy focus is placed on the heterogeneity in the Pakistani diaspora. This is exemplified through the case studies which include a wide array of Pakistani men, differing in age, socioeconomic statuses, religions, sects, sub-ethnicities, as well as sexual orientation. There is Anwar, an Ahmadi Muslim born and raised in America, Nadeem, a self-described “devout Muslim” living in Ireland, Omar, a Salafist getting a medical degree from Boston, Maliq, a second-generation Irish Sufi, Hamayun, a 20-year old gay Muslim who spent the first 14 years of his life in Pakistan, and many more. The stories of these men prove that Pakistanis and Muslims are not members of a homogenous community. Rather, they have their own stories and their own journeys.

There is heavy complexity both in the structure and the content of the book yet Dr. Considine explains the ideas in a very accessible manner. He is, however, careful in that he does not oversimplify ideas, maintaining the truth of the ideas. He also crafts these complex ideas in such a way that it does not leave the reader overwhelmed. Pakistani people are not the only ones who would gain from this book. The book is rich with knowledge that would enlighten and expand the mind of any reader. Perhaps the best part about the creation of this book is that it comes from a place of peace and tolerance. Dr. Considine dedicates it to the “bridge builders.” This book is a profound step towards doing exactly that: building a bridge. Dr. Considine deserves high-praise for the feat he has managed to accomplish with this book.

Craig’s book which comes out on July 11th has already been endorsed Baroness Sayeeda Warsi, who is a lawyer, politician, and member of the British House of Lords:

“Considine unpicks the complex journey of identity through the lens of the Pakistani experience both in the US and Europe. Placing both belief and bigotry in context, challenging both inter and intra community tensions and using the personal accounts of individuals he humanizes the monolithic myth of ‘the Pakistani.’ An important and timely contribution by a committed bridge builder.”

Dr. Mona Siddiqui, who is a Professor of Islamic Studies and Christian-Muslim Relations at Edinburgh University also endorsed the book saying:

“Pakistani Muslims are often seen as one of the most controversial ethnic and religious groups on issues of identity and integration. In this well researched and empathetic study of Pakistani diasporas in Ireland and the US, Craig Considine has made a valuable contribution to the literature on Muslims in the West and the language of `us’ and `them’ which continues to inform the political and social narrative of citizenship.”