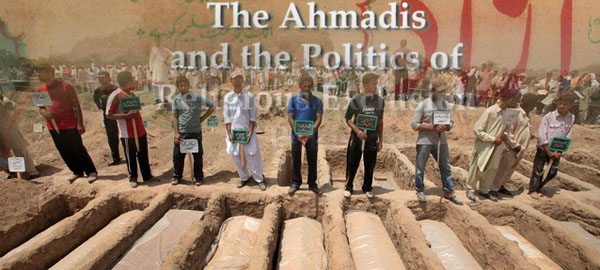

In this path-breaking new work, Ali Usman Qasmi, assistant professor at LUMS (Lahore University of Management Sciences) traces the history of the political exclusion of the Ahmadiyya religious minority in Pakistan.

According to a recent assessment of state persecution in Pakistan, the excommunicated Ahmadi community lost 39 members through murder in three years (2012-15). Forty Ahmadis were injured after assault and six were kidnapped. Eight Ahmadi graveyards were desecrated, 10 “places of worship” damaged, while harassment occurred in 11 cases. You can’t say “mosque” when referring to an Ahmadi place of worship if you want to avoid being thrown in jail. Ahmadis can’t say “Quran” or “namaz” either.

States at times practise exclusion, the majority considering “even the smallest minority within national boundaries… as an intolerable deficit in the purity of the national whole” (Arjun Appadurai). They do it through impunity or manifest legal devices; but Pakistan did it by excommunicating the Ahmadi community through the second amendment to the constitution (1974). In his remarkably even-handed book, The Ahmadis and the Politics of Religious Exclusion in Pakistan (2015), Ali Usman Qasmi, assistant professor at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Lahore University of Management Sciences, has told the story of how it happened.

It is fascinating how Pakistan’s Islamic teleology evolved as it distanced itself from the secular “afterglow” of the British Raj and zeroed in on what looks like a precursor phase to an al-Qaeda and Islamic State worldview in the 21st century. In 1953, when the riots against the Ahmadi community first led to the setting up of a judicial commission, the Grundnorm of the Objectives Resolution of 1949 had not yet been internalised, and the judges ended up delivering a humane verdict in favour of the victim community.

All Muslims seem to have an internal trigger that makes them backslide to Islamic Leviathan. Such a trigger was manifested in 1974 in a parliament dominated by a “socialist” Pakistan People’s Party led by a charismatic secular leader, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. The author provides evidence of the mystery trigger by narrating how Bhutto never attended the apostatising sessions of the National Assembly and actually “reprimanded” his attorney general, Yahya Bakhtiar, for unfairly prosecuting the Ahmadis till he was reminded that he had ordered the trial himself.

The 1953 anti-Ahmadi riots had been “organised” in Punjab by then Chief Minister M.M. Daultana, who made the most enlightened speech at the judicial commission, saying a community could be converted into a minority only when it asked for such exclusion. But evidence showed that his government had funded the riots. Then Prime Minister Khawaja Nazimuddin was forced by states aiding Pakistan to abstain from firing his Ahmadi foreign minister, Sir Zafarullah Khan, and said the following in rebuttal of the famous August 11, 1947 address of the founder of the state, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, to the Constituent Assembly, in which he had, in a manifestly Lockean speech, pledged a pluralist country where religion and state would be separated: “I do not agree that religion is a private affair of the individual nor do I agree that in an Islamic state every citizen has identical rights, no matter what his caste, creed or faith be… The speech of the Quaid-i-Azam must be interpreted in the context in which it was delivered.”

The dilemma in 1953 was that the clerics appearing before the Justices Munir-Kiyani Commission couldn’t agree on the definition of a Muslim. If they reduced it to the pronouncement of the “kalima” (the historic Muslim catechism), the Ahmadis couldn’t be indicted as they said it the same way as “normal” Muslims. If you insisted on it, however, the Shia could fall into the trap of apostatisation as their catechism of faith actually differs. The problem that arose in the post-apostatisation period was: How could Ahmadis be trapped into declaring themselves as non-Muslims on identity cards and passports?

Did Bhutto do it for Saudi money? His reference to the “solution of a 90-year-old problem” points to the “trigger” that hides in all Muslims. The Saudi push happened more clearly when in 1980, Zia took Saudi dictation to impose religious tax (zakat) on the Shia. The Rabita Alam Al Islami (World Islamic League), the Saudi organisation with billions of dollars on its budget, was active in 1974; it was active under Zia, too.

As noted by Vali Nasr in his book, The Shia Revival: How Conflicts within Islam Will Shape the Future (2006), the anti-Shia edicts (fatwas) were “managed” through a scholar of India, Manzur Numani, then head of the Nadwatul Ulema of Lucknow, who compiled anti-Shia fatwas of apostatisation from the major seminaries of India and Pakistan in 1986. This compendium of fatwas laid the foundation for Shia massacres in Pakistan. Who is next?

The peaceful Ahmadiyya Community has suffered a great deal at the hands of the very people either themselves or their fathers who opposed even the Idea of Pakistan, they even called the founder of Pakistan Qaid e Azam as Kafir e Azam. Because the decisions made by the successive Governments to secure their own position in order to hold on their seats by declaring Ahmadiyya Muslim Sect as non muslims to please the clergy who are the very people described above. This has caused the present day calamity in the country there is no peace and every day that goes by there are conflicts between various other sects and it is further causing unrest in a already troulbed land. Among all this Ahmadiyya Community suffers the most because the Mullahas and the Mullahs banned outfits find it easy to cause unrest in the country to further their aims to blame Ahamdiyya Community for their own misdeeds and unrest.